I have been a horse trainer for twenty years, and a runner for ten. Having to compete at horse shows fills me with dread, but I register with happy anticipation for trail ultras. Why is the competition in ultra running so much friendlier than in equestrian disciplines? The simple answer is this: less money is involved, and less subjectivity. By money, I don’t mean prize money. In this regard, dressage and ultrarunning are remarkably similar. However, the expenses for training and competition are in two different leagues.

To get started, an aspiring trail runner will purchase a pair of shoes and a handheld water bottle. A hydration pack might follow, or several hydration packs, until one really works. Torn between the laws of fashion and those of function, a runner will accumulate a closet full of minimal shoes, maximal Hokas, shorts, skorts, bra tops, jackets and shirts in matching colors, as well as a drawer full of technical socks, all in dusty brown and not all of them matching. Add race entry fees, travel costs, piles of gels, and large jars of whey protein and vaseline, and many will argue that ultrarunning is not a cheap sport.

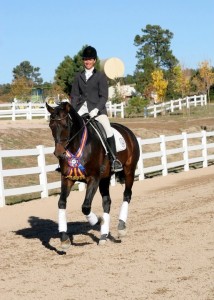

A horse costs anywhere from what you pay for a small used car to more than a large new house, and has living expenses similar to your own, except that it needs four shoes every six to eight weeks. not just two. Add a saddle, tack, and trailer. And this does not include coaching for you, or training for your horse. You will now agree that trail running is a cheap sport after all, compared to equestrian competition. Once you have invested your life savings in a hobby, the pressure to do well increases.

An even more important factor is the fairly democratic nature of ultra running. If you train more, and more wisely, you will improve. If you slack off, you will not. Money is useful, but only to a point. If you can afford to pay someone to clean your house, you can run an extra couple of hours. Extra dollars can buy better shoes, cuter outfits, coaching, and treadmills. But you still have to go out there every day, log mile after grueling mile, and discover what you’re made of the hard way.

Even the best treadmill will not prepare you for rocky terrain, steep climbs, gale-force wind, sleet, river crossings, hypothermia, heat exhaustion, blood blisters, face plants, or getting lost in the dark. There is no placebo for these experiences. And this is what keeps ultra running fair and the competition friendly. When someone passes you in the last few miles of a 50-miler, it is because because you have gone out too fast and are now paying for it, not because she was able to afford a better pair of socks. When you pass a fellow runner who is vomiting margarita-flavored Clif Bloks into the bushes, you will not feel smug and superior, mainly because you know you could be in the same unpleasant position a few miles from now. The playing field is really quite level.

In dressage, enough money can buy a much more tangible advantage: a talented, already trained horse, tuned up, fit, and ready to compete. To fully comprehend the implications if such a thing were possible in ultrarunning, imagine a future where body parts are easy to exchange. A set of legs and a pair of lungs can be transplanted back and forth between people in a quick and painless but still very expensive surgical procedure. In such a world, an wealthy. ambitious newbie ultrarunner could take shortcuts. He could buy the fitness he needs without having to go through the trouble of training a flabby, inexperienced, and undisciplined body from scratch. Instead, he would start out on a pair of schoolmaster legs, purchased from a seasoned and accomplished veteran, to learn what ultrarunning feels like. Then he would retire or resell these legs and move on to a younger, very talented new set. Mistakes become much more forgivable this way. If you skimp on warmup or cool down, if you beat up on one pair of legs physically or psychologically to where they refuse to run as well as before, you simply move on to a new pair. Imagine the starting line conversations: “Did you see her legs? Just imported from Europe, I hear they used to be Kilian Jornet’s. Of course she has to get them waxed every five minutes…” The gloating new owner of said legs struts by at that moment, stifling further catty comments. When she wins, whispered speculations ensue. Will she keep winning? Or will she trash these legs and move on to a new pair? Once money can buy a significant head start, the competition becomes less pleasant.

The second part of the puzzle is that dressage is a judged event with very subjective standards based on correct execution of movements and the judges’ aesthetic impressions. Runners compete against the clock. Ultra runners, in addition to the clock, often compete against the desert, or the mountains. The clock never lies. The mountains are equally tough on everyone and impressed by no one. If runners were like dressage riders, they would be judged instead on their style, leg turnover, cadence, and general fitness and appearance by a panel of judges sitting in booths along the ultra route at crucial points of the course, like the last climb at mile 90 or the top of Hope Pass. Each runner would receive a score between 0 and 10 for each segment of the course, along with a brief comment, which may range from benignly condescending to openly contemptuous, e.g:

-Runner has lost elasticity in her steps.

-Needs to move feet quicker and lift them higher.

-Seems reluctant to keep climbing.

-Stumbled. Needs better balance.

-Desire to move forward is not apparent.

-Neon pink shorts and flyaway hair distract from overall positive impression.

-Runner not adequately prepared for this level of competition.

And so on. At the finish line, the highest average score determines the winner. Scores of 70 and over earn the big buckles. To ensure fairness, the judges undergo a rigorous qualifying process. They have to practice their judging skills in many shorter races before being allowed on the course of such prestigious competitions as the Western States 100. And the judging standards are based on time-honored, classical principles of distance running, starting with Pheidippides.

How would this change our sport? Very probably, the actual placings, especially, near the front, would not change very much. People like Timothy Olsen and Ellie Greenwood would get high scores. They would still win, maybe more under some judges than others. They are fast because, among many other factors, their form is flawless. They look like highly trained ultra runners because that’s exactly what they are. So why not focus on style instead of speed?

Because the clean-cut nature of the competition would go away. Quibbles about the judging standards would become common, especially among slower runners who look more like ordinary humans and participate because they enjoy it. Most judges would not really care how these runners scored, and many judges would think that such middle of the pack plodders should not run ultras in the first place. Many discouraged runners would quit entering races altogether. Ultrarunning would become a very exclusive club.

And this is why, after more than 20 years in the horse business, I choose to take a break from professional training and competing. I am leaving the exclusive club. I will always love horses. But the sport of ultrarunning is indefinitely more rewarding in terms of fairness, camaraderie, and joy.

Simply awesome!! This story makes a ton of sense!!