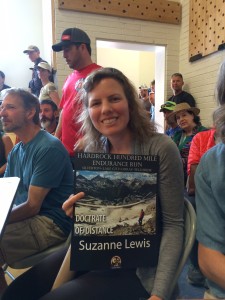

Seasoned veterans of ultra running are an opinionated bunch. They argue about shoes, training, and nutrition. Some swear by Hokas, some by Luna sandals. Some survive on gels for 20-plus hours, others prefer bacon bits. But they all agree on one thing: The Hardrock 100 is one of the toughest, roughest, most challenging 100 mile runs out there. The loop course follows old mining trails through the San Juan mountains of Southern Colorado. Runners move above treeline for much of the race, through snow fields, swamps, and thunderstorms, climbing and descending 67 000 feet of elevation change in the process. In spite of all this, over 1000 qualified, undeterred hopefuls enter the lottery every year to compete for 152 entry spots. For the second time in a row, my friend Suzanne Lewis got lucky. I, on the other hand, didn’t even make it onto the wait list. I was in a funk, lamenting the unfairness of lotteries and of life in general, until Suzanne asked me to be her pacer for part of the race. The next best thing to running the Hardrock is to share the Hardrock experience. Even if you’re just running a third of the course, it’s still epic. It’s still exhausting. It’s still unforgettable. Here are the gory details:

Thursday, July 9,

7 p.m. River House, Silverton.

I arrive in Silverton, where Suzanne and her boyfriend David Hayes have already spent a full week to adjust to the altitude. Their friend Pete completes our team. We finalize the race plan over heaping plates of spaghetti with tomato sauce. Suzanne is excited, but all business. The plan in a nutshell: David will drive and organize. I will pace from Grouse to Telluride, mile 42 to 73. Pete will take Suzanne from there to the finish.

9 p.m.

Lights out! We ultra runners are such party animals.

Friday, July 10

4:30 a.m.

While enjoying a bowl of oatmeal, the breakfast of champions and her last real meal for the next couple of days, Suzanne checks off her list: lube feet, check contents of pack, ponder which layers of clothing to take along and which to leave in the crew bag. We add my lucky turquoise earrings to her race outfit. Nothing can go wrong now. Before we know it, it’s time to head over to the race headquarters for the mandatory check-in.

5:10 a.m., Silverton school gym

Our little group files in, along with other runners and their crews. Nervous chatter. Last-minute pit stops.

The clock is ticking. Predicted winner Kilian Jornet in a circle of fans, posing for pictures. I find other friends who are running today: Margaret Gordon, Leah Fein, Missy Gosney. Quick hugs, good wishes.

5:45 a.m.

152 runners and their crews file out the gym doors.

6 a.m., Hardrock 100 starting line outside the Silverton School gym.

They’re off! David and I run ahead to take some pictures, then make our way to the first aid station, ten miles and one big climb into the race.

8:30 a.m, Cunningham aid station

We arrive in time to watch the front runners cross Cunningham creek.

Suzanne comes in an hour later, on target for a 40-hour finish, spirits high, running strong. We refill her bottles, remind her to eat, and she’s gone. We won’t see her again until mile 42 at Grouse Gulch, around 6 p.m. at the earliest.

11 a.m., Café Mobius, Silverton. Time for a latte and a breakfast burrito.

12 noon., River House, Silverton.

We have four hours to kill. The Hardrock online tracking is down, but we follow irunfar’s Twitter feed. I pack my gear for a night’s worth of pacing in the mountains, then take a prophylactic nap.

5 p.m. Grouse Gulch aid station, mile 42

Dark clouds hang over Handies Peak. We’re early. The weather is slowing everyone down. It’s raining. It’s cold. We wait, among the anxious crews of other runners, doing our best to keep ourselves and the contents of the crew bag dry.

8 p.m.

The evening sun has disappared behind the mountains. Suzanne arrives, exhausted, drenched, and depleted from a climb up Handies in the thunderstorm. Time for hot soup, long tights, encouraging words. We head out into the falling darkness, up the dirt road toward Engineer pass. We haven’t really seen each other since I paced her at last year’s Hardrock, so there’s lots to talk about.

10 p.m. Suzanne casually informs me that she is thinking of dropping out at Ouray. Alarm bells ring in my head. She is moving well, but her stomach has stopped cooperating. She says she is tired of pushing herself, of trying so hard. Arguing with her is useless, so I try to distract her with ginger chews and different conversation topics. No success.

11p.m.

We turn onto the downhill singletrack toward Engineer Pass. It’s a slick, muddy descent, which I realize when I land on my behind and continue on down the trail looking like I’ve soiled my tights but otherwise unscathed.

11:30 p.m. Engineer aid station, mile 48.7

Suzanne sips broth with crackers. Minor blister surgery by the campfire. A quick stop.

12 midnight. Long descent into Ouray.

It’s a beautiful night. The storm clouds have lifted for now, and we run under a blanket of stars. A narrow moon hangs over the jagged silhouettes of the San Juan mountains. Suzanne is running strong because she is in a hurry to get to Ouray, where she still plans to drop. I remind her of all the reasons to finish. I remind her of how motivated she was just this morning. She reminds me of how many steep climbs still lie ahead in the remaining 50 miles. We are both right, and we both know it. The argument deadlocks.

1 a.m. Saturday, June 11. A new day.

When running in the dark, I like to use a handheld light in addition to my head lamp, and I have just bought a nice new Fenix at REI. Now, I set this down on a rock while I use both hands to help Suzanne take off her jacket. We continue on our way to Ouray. It takes about a mile before I realize I have left the Fenix. About thirty minutes later, a runner catches up to us.

“Did either of you lose a flashlight?” He asks. I feel overwhelmed with gratitude. This episode confirms my theory that ultra runners are more honest than the average population.

2:30 a.m. Ouray, mile 56.6

Suzanne is still feeling cold, still low on energy and motivation, still wants to quit. She sits down in a folding chair. David and I wrap a sleeping bag around her, feed her soup and pizza, and try to convince her otherwise. We’re surrounded by runners who look much worse than she does, runners who are shivering, vomiting, cramping, bleeding. Some of them probably should drop, but want to keep going. Suzanne, strong and uninjured, should keep going, but wants to drop. She spends an hour at the aid station, hiding under a blanket and repeating that she can’t go on with mulish stubbornness. We know she will hate us in the morning if we let her do it. Reasoned argument is useless. We use manipulation, bribery, veiled threats and lines from Monty Python until she finally decides to get back up and back out into the night.

4 a.m.Somewhere on the long, uphill dirt road toward Virginius Pass

It’s the darkest hour before dawn, in every sense of the word. We climb slowly. Suzanne keeps trying to turn back toward Ouray. I keep insisting, patiently, that we go up the mountain. Like a horse that does not want to go load into a trailer, Suzanne refuses and resists, but eventually gives in. Unlike a horse, she does not want a carrot or other treat as a reward. I wish she did. A few hundred calories would improve the situation.

4:45 a.m. Suzanne keeps yawning. Her sleepiness is contagious. I try to get her to eat bites of Stinger Waffles, in which she shows little interest. Her steps are unsteady. At one point, she trips and falls down the embankment, which wakes her up for a while, but not for long.

5:30 a.m.

Daylight on the horizon, a source of new energy for Suzanne. We are still climbing slowly, but at a steadier pace. Meanwhile, in Silverton, Kilian Jornet has already kissed the rock after demolishing the course record.

7:30 a.m. Governor Basin aid station, mile 63

We have decided that a five minute power nap might be the best strategy. The wonderful group of volunteers is cooking eggs and potatoes in a crock pot. Suzanne’s appetite makes a comeback. She finally eats, then curls up in a folding chair while I enjoy a lavish breakfast in the morning sun. Five minutes turn into ten, but the short break does the trick: Suzanne’s motivation returns. We chug some coffee, slather on some sunscreen, and begin the steep climb up Virginius Pass with optimism and silly jokes, laughing like teenage girls and moving quickly. We begin to pass people.

9:30 a.m. Virginius Pass, mile 68

Using our hands and a rope, we scale the almost vertical last piece of uphill to Kroger’s Canteen. The volunteers cheer us on from the top. One of them turns out to be my old friend Allen Hadley. He tries to interest me in a “pacer special” shot of Tequila. Someone starts singing “Wasting away again in Margaritaville” others chime in. A surreal scene on the mountain top. But Tequila and I don’t have a good relationship, not even at sea level, so I turn down the offer.

We wave goodbye. Five downhill miles to Telluride.

10.30 a.m. Singletrack through beautiful aspen forest above Telluride.

Telluride is a fancy sort of place. It has a city ordinance that makes sleeping in cars illegal. We speculate that looking like homeless bag ladies is probably against the law, too, so we try to tidy up our grimy, muddy, disheveled selves before hitting the pavement. Our efforts are pointless. We’ve been running in the mountains all night, and it shows.

11 a.m. Telluride aid station, mile 73.

Pete is waiting to pace Suzanne the last 27 miles to the finish. Part of me wants to keep pacing, but other parts – i.e. my quads – remind me that I have not completely recovered from Western States, exactly two weeks ago. Suzanne’s spirits are high. She is ready to get it done. We hug. She sheds some layers, refills her bottles, and they take off. David and I load up the crew bags, then drive back to Silverton.

2 p.m. Silverton, River House

Sandwich, shower, a bit of sleep. We’re tired, and we’re not the ones running 100 miles. The online tracking is up again, but hours behind real time. We are guessing Suzanne’s finish time will be after midnight.

11 p.m. River crossing, mile 98

We know we’re early, but we’re too jittery to do anything else, so we wait for Suzanne out here. A lone volunteer named Guillermo is in charge of helping runners cross the river and then cross the road. He’s lost count of how many hours he’s been awake. We don’t expect Suzanne for at least an hour, so we take over. Guillermo goes to his car for dry shoes and a few minutes of sleep. We sit in the dark, scanning the hills for head lamps. The river is waist deep, the current strong. With only two miles to go, it must feel like one final insult to battered, exhausted bodies. Runners hang onto the rope, stumble ashore, soaked but elated to be almost done.

1 a.m. River crossing

Suzanne and Pete have arrived! Suzanne has made a remarkable comeback. She looks strong, sounds coherent. Pete says no runners have passed them since Telluride. We wake up Guillermo, then drive back to Silverton.

1:25 a.m. Finish line

David and I meet Suzanne and Pete about half a mile out. We want to run the last stretch together. Suzanne, on what must be her last reserves, runs so fast I can barely keep up with her. She kisses the Hardrock at 1:23 a.m. — 43 hours and 23 minutes after the start. What an accomplishment. What a way to persevere.

5:59:59 a.m.

We’re asleep. The last Hardrock finisher kisses the rock, just one second ahead of the 48 hour time limit.

Sunday, July 12

Time to go home. I feel reluctant to leave Silverton and all its Hardrock stories behind.

The Hardrock 100 is an epic adventure. Runners reach their limits. Their bodies hurt. Their minds retreat into dark places. Their spirits crumble. Their emotions, stripped of any protective layers, become raw, exposed to the elements like the bare mountain tops of the San Juans. But that’s not the end. Hardrockers persevere. They reach a place beyond pain. They find new energy in hidden corners of their ego. They learn to build a bright new fire from the ashes of despair. It’s a beautiful thing to see. Thank you, Suzanne, for allowing me to be a part of this experience. Thank you, all my old friends and new friends, for being there. Thank you, everyone out in these mountains, for making the Hardrock 100 possible. I will put my name in the hat once again this December, hoping to get picked. But I know I will feel both elation and utter terror if it really happens.

It’s a good time to be alive and running.