“The thing I don’t like about Western States is that you show up at the

starting line in the best shape of your life and a day later you are in

Auburn in the worst shape of your life.”

– Andy Black

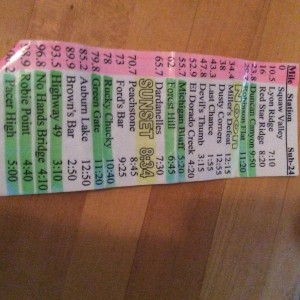

June 29, 2013. This is it. During the six months since getting lucky at the Western States lottery, I have logged over a thousand miles, injured and rehabbed my IT band, worn out a pile of running shoes, been labeled insane, gone through serious heat training in the Moab desert, serious hill training in the Grand Canyon, and several phases of serious nail biting and soul searching. I want to run this race well. Western States is not just another 100-mile run. Western States is the grandfather of ultra marathons. Even before Western States, there was the Tevis Cup endurance ride. Since the late 1950s, the toughest, fittest horses and riders have raced every summer from the mountains of the Sierra Nevada to the town of Auburn in a single day, along100 miles of rugged trails through a series of deep, steep canyons in temperatures that can easily reach three digits.

In1974, Gordy Ainsleigh’s horse went lame the day before the event. Rather than watching from the sidelines, he set out on his own two feet. No one knew whether such a thing was possible or not. Gordy had never run a marathon. Gels, hydration packs, and other useful items any endurance athlete takes for granted today were not invented yet. He drank from streams and subsisted on a race diet of canned peaches, but still finished among the middle-of-the-pack horses in just under 24 hours. Gordy had such a good time that he did it again the next year, along with a couple of friends. A few more joined them the year after that, and modern-day ultra running was born.

By 1977, the Tevis Cup ride and the Western States run had grown into two separate events held on two separate dates, but the award for finishing this oldest, most prestigious of all 100-mile foot races is still a belt buckle. The color is important: it’s silver if you finish in 24 hours or less. Finishing in under 30 hours still gets you a bronze version. Both are by now such hot commodities that non-elite runners have to qualify for the chance to throw their name into the lottery hat. Every year around three thousand hopeful souls apply. Of these, a few hundred lucky ones get to start, and about two thirds of them finish. In 2013, I was lucky. Here I am, ready or not.

As part of our tapering program, my training partner Rachael and I have road tripped to Northern California from the Southwest, through Las Vegas (Nevada), Death Valley, and Yosemite. After a few days of ghost towns, aliens, Anasazi spirits and fake European monuments, the prospect of 100 very tough, very hot miles seems real and daunting, but it is too late to change our minds now. We have weighed in. We have signed all the waivers describing in great detail what might happen to runners who show up underprepared, or who underestimate the terrain. The risks include, but are not limited to, death by gruesome causes like cougar attacks, heatstroke, kidney failure, and other scenarios we laugh about over our last — maybe last ever — pints of beer. It’s a downhill course, how hard can it be? Alcohol inflates our confidence. We think we are ready for a day’s worth of mental, emotional, and physical highs and lows that follow the jagged elevation profile. We are wearing, almost flaunting, our plastic ID bracelets. The drop bags are dropped off. This is it.

Race day begins at 4 AM in Olympic Valley. It will, if everything goes as planned, end sometime the next morning on the High school track in the town of Auburn, 100 miles further west. After we pin on our numbers, the small group of runners from New Mexico meets for a pre-race photo: Ken, who looks like a science geek but has, on his skinny legs, finished many tough mountain hundreds like Hardrock and Leadville, is our best hope for a silver buckle time. Eric, the only one of us wearing a shirt with a Zia symbol on it, huddles with his wife for last-minute crew instructions. Ian, age seventy, has finished this race a dozen times in his prime and hopes for one more encore. His white beard and matching ponytail give him the air of a very fit Santa Claus. Rachael, at five feet ten towering over all of us except Eric, her red mane in braids, checks and rechecks the contents of her pack. Sunscreen? Toilet paper? Band-aids? Ginger? Salt tablets? Yes, yes, yes, yes, yes. She and I have spent a lot of time debating what to wear in terms of function, and of fashion. Our running skirts have similar but not matching flower patterns, and we have coordinated the color of our sport bras with our Hokas. We are well-dressed for whatever happens out there.

This is it. Time to head to the starting line. Living legends surround us. Gordy Ainsleigh wears the number one. He is now in his sixties, with a grizzled beard that almost matches Ian’s, but he still runs his race every year. Next to Gordy walks the Cowman, another Western States pioneer, easy to spot because of his Viking helmet, horns and all. The elite runners, some of whose faces we recognize from the pages of Ultra Running magazine, get to enter without going through the lottery process. Most of them carry nothing but a small water bottle and look like genetically modified super humans, all muscle and grit. We won’t see them again: the fastest men will finish in under 16 hours, the fastest women in under 18, light years ahead of normal people like us. Now they appear mortal, at least Nikki Kimball does, as I watch her move along the bathroom line two spots ahead of me.

Five minutes to showtime. I hug Rachael. I kiss David, my crew-pacer-photographer-husband combo, who then sprints ahead to take a few action shots before gathering the rest of our crew and driving to Robinson Flat. I hope to see him there sometime before noon. Good luck everyone. Break a leg. Not literally. Run strong. Wind at your back. Remember to start your Garmin. At 5 AM, the very first sliver of daylight shows on the horizon, and the starting gun sends almost 400 runners up the mountain into the wilderness. Every one of us hopes to reach Auburn by 10 AM the next day, after watching the sun rise, set, and rise again.

I take off running but slow to a hike almost immediately. The climb up Emigrant pass is steep, and with over 99 miles left to go it seems unwise to waste energy. A gorgeous view of the morning sun in shades of red and gold over Lake Tahoe greets us at the summit. I settle into the conga line leading down the single track, crunch over patches of melting snow, cross muddy spots, splash through puddles and fast-moving creeks. My shoes, saturated, make squishing noises, and my feet are soaked. So is my midsection, when the hydration pack hose begins to squirt an unexpected stream of water down my shirt. What the heck is this? The bite valve has fallen off for no apparent reason, and I spend precious minutes looking around for it among grass and slush and mud, visualizing my slow, painful death from dehydration in the forecast high temperature of 102 degrees. The prospect fills me with panic, as does the image of my obituary in the local newspaper: “croaked without ever accomplishing anything worthwhile, most notably without finishing Western States, where she didn’t even make it to the halfway point.” Crud. Oh, wait, doesn’t the system have a shut-off valve? Yes, it does. My heart rate goes back down to normal. Drinking involves both hands and some additional effort from now on, but it’s still possible. Also, I remember that a spare bite valve is waiting in the crew bag. Deep breath. Today is not my day to die, at least not before ten a.m.

The morning is still cool and crisp, a calm before the inferno, and a good time to move up a little. I squeeze by a pony-tailed kid with a snake tattoo on his shirtless back and a mud-splashed woman in orange compression socks. In front of me appears a familiar silhouette wearing a bubble-gum colored ruffled miniskirt over very muscular and very hairy legs. Keith, the man in the pink tutu, is among the most photographed people in any ultra he runs. He always offers a smile and a chat, even while climbing the Red Star ridge. “Hokas working out for you?” he nods in the direction of our matching brand of clown-like footwear. We debate the respective merits of the minimalist and maximalist shoe philosophies, the Grand Slam, and his choice of clothing: “It’s good ventilation, and it makes running 100 miles look easy.” I tag along as he sneaks up behind a tall, hardcore-looking runner with cropped hair, no apparent body fat, sleek wraparound sunglasses, and the efficient stride of a gazelle. Keith clears his throat, politely mutters “on your left”, then leaves him behind without effort, ruffles bouncing. No, he wears his outfit to demoralize those who take themselves too seriously. Getting dusted by a middle-aged bald guy with a British accent and a pink ballet skirt will destroy any delusions of grandeur, including mine. I can’t keep up, and he fades into the distance, waving a cheerful good-bye. The hardcore runner and his injured pride take off after him. My legs are itching to do the same, but I stick to my goal pace. “Run your own race” is a good mantra for this one. Trying to keep up with other people is a recipe for disaster. I’ve learned this the hard way. Not today. Today is a day to be smart.

One marathon done, only three to go. I remember to eat some clif bloks, but drinking is complicated: open valve with the left hand, while pinching the hose with the right, then try to suck up water without spilling most of it. Too much trouble to be worth the effort. Is water really necessary? Nah, if camels can live without it, so can I. So much for being smart today.

The trail snakes down into a wide valley where it gives way to a dirt road. Cowbells sound in the distance, announcing the first major aid station. Sure enough, a tent and a timing mat come into view. Robinson Flat, mile thirty-one. The place is buzzing with energy and eager volunteers in green T-shirts. Aid stations at Western States are a cross between a pit stop in a formula one race and an open air festival. Crews have settled in on camp chairs and blankets spread out on the grass, coolers between them. “Looking strong” David observes as he emerges from the crowd and runs in with me. Our other two crew members, my undertrained stepson Bobby, home from college for the summer, and Ken’s iron woman wife Margaret, greet me with high fives as I weigh in at five pounds less than this morning. Not good. I am not a camel after all. Could be worse. We are an efficient team: choke down some watermelon, stash more clif bloks in front pocket, refill camelbak with water, add electrolyte tabs, replace bite valve, put on cool tie, dump ice cubes from cooler into hat and other strategic places. Group hug. I’m off to take on the canyons. Two minutes total, neither of them wasted.

It’s getting hot, but I feel prepared for oven-like conditions. The bandana around my neck is doing its job, and the ice inside my bra is slowly melting. The scenery has changed from alpine to mediterranean. I pass gnarled trees, pastures with brown dots that move on the hillside. Are those cows or horses? Sightseeing comes at a price. A root catches my toe and sends me tumbling down the rocky trail head first. I slide to a halt, face inches away from a cow patty, which answers my question. Ouch, but everything still works. Could be worse. I scrape dirt, blood, and pebbles off my knees. The damage is not worth my emergency band-aid.

Inclines are becoming steeper. Duncan Canyon yawns, then my jaw drops at the sight of the Devil’s Thumb rising across from me. It looks like its name, no false advertising here. Several runners, Ken among them, are cooling off in the river before the climb. A good idea, but the blister gremlin likes wet shoes, so no thanks. I have lots of time to regret this decision as Ken and I struggle up the almost vertical incline in the sweltering heat of midday. In retrospect, the blisters might have been more tolerable. We pass a pale, motionless figure stretched out on a log by the side of the trail, face up, classic corpse pose. “You okay there?” On closer inspection, I recognize the mirrored wraparound Oakleys pushed on his forehead. Mr. Hardcore couldn’t keep up with Keith and his tutu after all. Concerned questions and some gentle prodding elicit a weak thumbs-up sign. A squirt from Ken’s water bottle finally does the trick: a mop of sweat-crusted hair begins to shake, and unfocused eyes squint in our direction. We offer electrolytes and encouragement, which brings him back into an upright position. He mumbles a thank you and staggers on. Maybe it would have been kinder to leave him, I think a bit later, as I look at trailside spots suitable for curling into the fetal position. My stomach, which has been cooperative so far, decides to throw a tantrum. I can taste an odd mix of partially digested peanut butter, margarita-flavored clif bloks, and watermelon fumes in the back of my throat. This toxic cocktail moves up and almost out at random intervals, then goes back down. Adding citrus-flavored water to it does not improve the situation. It’s a shared misery. We count three runners vomiting into the shrubby vegetation. One of them is Luanne, former winner of Western States, now in her fifties and still competitive, but not today. You okay? Yeah, don’t worry about me. We continue, one step at a time. I come close to puking. Watch out, Ken, don’t wanna hit your shoes. Waves of nausea come and go. Sweat dries in a crusty layer on my face and seeps into my eyes, which makes them burn. On the plus side, I am still moving. Left foot. Right foot. Alternate. This seems more complicated than usual. Focus, dammit. Left. Right. Conversation grinds to a standstill. We have no energy for anything but grunting noises, but we keep going.

After traversing hell for what seems like (and probably was) several hours, we reach heaven, where friendly angels in green T-shirts drape a cold towel around my neck, hand me the world’s best popsicle, and remind me to drink more. I come close to experiencing a religious conversion, but after a few minutes, my core temperature drops. Saint-like but human aid station volunteers come into focus. I force a boiled potato down my dry throat into the still protesting stomach and walk away. Ken tries to coax me into a run, but the potato is unsure of which way it wants to go, and I would rather barf in the privacy of my own port-a-shrub than in front of him. Besides, the 24 hour goal is still within his reach. Go for it, go on already. As Ken disappears around the next switchback, my stomach finally expels all of its greenish, slimy contents down the next canyon. Good riddance. I keep walking, drinking, wishing for a toothbrush, and chewing pieces of ginger. The sun still glares straight down without mercy, and the air still sizzles, but for some unfathomable reason I feel more human again. The climb up Michigan Bluff, though longer, seems less grueling than the one up Devil’s Thumb. I drain almost my entire supply of water, and feel hungry enough to consume more clif bloks, as long as they’re not margarita flavored. By the time the next aid station comes into view, I am reenergized and no longer worried about worrying my crew.

Mile fifty-five, more than halfway there. My weight is back up to where it was this morning, and my stomach, in a much more cooperative mood, agrees to a few bites of turkey sandwich. I fall into a chair, for the first time since 4 AM. David’s job is to force me back into action in five minutes, no matter how much I beg him for more time. Dry socks feel amazing, as does more ice and cold water. Only one small blister so far. Reassured and refreshed, I head out.

The descents begin to hurt, but the sun is finally losing some of its blunt force. I reach Foresthill around 7:15 pm, still feeling strong. Mile 62. Margaret is waiting, already wearing the pacer number, and we exit at a brisk trot. The trail is beautiful in the evening light, rolling and smooth. For several miles the 24 hour goal moves within reach once again, until, out of the blue, my quads decide to quit cooperating with the other, still functioning parts of my body. They are done with downhills, done with being abused, done with running altogether. Muscle cramps grip my legs like iron claws. As darkness falls, my energy level plummets. The pain is so intense I almost cry, and for the next ten slow, excruciating miles, I walk, shuffle, walk again. I whine. I complain. I curse in German, and in English. Margaret is probably tempted to abandon me to the carnivorous wildlife prowling the forest, but she doesn’t. Instead, she uses the kind of reassuring phrases parents use to calm down their sniveling, snotty-nosed offspring on long hikes or car trips: Yes, we have done three quarters of the race already. No, I am not the biggest wimp she has ever paced. No, finishing Western States in more than 24 hours will not make me the laughing stock of the ultrarunning community. Yes, we have already gone at least a mile since the last aid station. Yes, the next aid station is right around the corner. My addled brain suspects her answers may not be entirely honest. Even so, they propel me forward. Anyone walking still beats anyone crawling, and anyone crawling still beats anyone who stops. The 24 hour mark slips once more into the realm of fantasy. I don’t even care, I just want to finish. Or lie down and sleep. Or be devoured by a bear. Or a cougar. Anything to end this misery, anything but run. The last five miles to Rucky Chucky expand into at least twenty miles miles of agonizing torture.

There are stairs leading to the river. My quads recoil at the sight of them. But once I have stumbled down, cold water to my waist feels surprisingly refreshing, and the sight of people in wetsuits standing in the river all night, helping runners find their way along the treacherous and slippery rocks fills me with overwhelming gratitude. Dry shoes are waiting in my drop bag. My legs feel refreshed, or maybe just numb, as we hike up to Green Gate. Luanne has come back from looking like death at Devil’s Thumb. She passes me, her stride steady and confident, and invites me to tag along for a still possible 24 hour finish. Optimism returns. David takes the pacer number from Margaret like a baton in a relay. Let’s go already.

Once the effect of the cold water wears off, my quads begin to scream again. There is nothing to be done about it. I slow to the fastest walk I can manage, watch Luanne and the last sliver of silver buckle dreams disappear into the dark, and try to convince myself once more that bronze is a fine color for a belt buckle. The night is warm. Moonlight filters through the trees, creating a lace pattern of pale light on the trail. David reminds me to keep moving, and to keep hydrating. He knows his job. To keep me going, he garnishes lots of positive reinforcement with bits of sarcasm and threats. You really want to be last? Looks like it. No? Ok, then pick it up a notch. And another. He and I spend a romantic couple of hours speed hiking through the forest. The velvet darkness is alive with the sounds of crickets. A deer ambles across the trail and glances in our direction with mild surprise. In spite of my trashed quads and what by now feels like a huge blister on my left foot, a deep sense of joy and peace spreads inside me. We pass a limping dark-haired girl on the verge of tears and her determined pacer. Keep it up. Good job. Neither of us has the energy for extra words, but the shared exhaustion creates a bond that goes deep.

The next aid station blasts Christmas songs. A cheerful elf in the familiar green t-shirt and a Santa hat patches up my blister while I sit in a folding chair, under strings of twinkling multi-colored lights slurping a cup of ramen noodles to the sound of Rudolph the red-nosed reindeer. Several runners with complexions ranging from pale gray to olive green are curled up on cots or sleeping bags spread on the ground, their race over. I feel fortunate to be able to move, however slowly.

We jog, walk, and jog again. My head lamp dims, and a branch slaps me across the bridge of my nose. I pay no attention. Rock music sounds in the distance, and the hum of a generator. Brown’s Bar, mile 90. Time for a battery change. Someone asks me politely if I would like to clean the blood off my face, but battle wounds mean I am still a tough chick, though not a sub-24 tough chick. No thanks. I’m fine. Really. Ten more miles. The finish becomes imaginable. I manage a slow trot, then climb toward the highway 49 crossing, a good excuse to walk again.

As per race plan, David hands the pacer number to his son at mile 93 and gets in the car to position himself for finish line pictures. I know Bobby is excited about crossing the finish line with me, but he is a pacing virgin. What is good pacer etiquette, he wants to know. “Don’t be too nice” is David’s last piece of fatherly advice, but compassion with others is in Bobby’s nature. He can’t help it. “If you feel like stopping for a few minutes, let me know.” No, no, no. If I feel like stopping, kick me. Hard. Promise. Appalled, Bobby shakes his head, his eyes wide. That’s ok. While my ground speed is that of a geriatric snail, I have plenty of motivation to get this race done. I try to focus on the beauty of the darkness just before dawn, rather than my now totally defunct quads that act more like hamburger meat than muscles. The blister gremlin has grown into a blister monster, and he has invited its friends for a party. They have taken over the soles of both feet by now. My legs hurt so much more than the blisters that my brain is unable to focus on both pains at once. This is a good thing. More climbing, which hurts. More descending, which hurts worse. This has to be the last hill. I find the energy to run across No Hands Bridge at dawn. Three more miles, a 5k. Anyone can run a 5k. I have run 97 miles, I can manage three more. Bobby agrees. Breathe. Move. Another uphill. Another downhill. Another sunrise. We turn off our lights. Yet another hill. A paved road. Houses. Sidewalks. Like a tired horse on its way home, I smell the barn, enough of an incentive to trot a few steps at a time. Robie Point. One more hill. One more mile. I begin to think of finish line pictures, wonder how my hair looks and whether the salt crust on my face doubles as makeup. I am also grateful that photographs are not the scratch and sniff type.

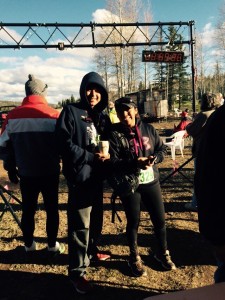

The stadium appears. I have dreamed of this moment since December and start running around the track, breaking into an all-out sprint that on the video turns out to be a shuffling jog. The finish line clock says 24:58. Less than an hour off my dream goal. David beams from behind his camera. I collapse on the grass, happy, exhausted, exhilarated, and drained of all reserves. One of the most grueling and wonderful days of my life is over. I cannot wait for the next chance at the silver buckle.

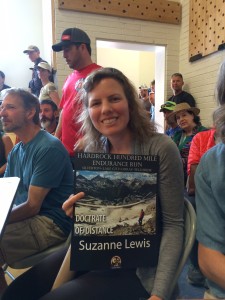

One by one, our group reunites. News trickles in. Each of us, and everyone else we see hobbling around, has a story worth telling. Joy, pain, defeat, triumph, despair all condensed into thirty or fewer unforgettable hours. Ken sits on a plastic chair, beer in hand, his feet in a purple kiddie pool full of ice water, a picture of contentment. His time was a smoking 23:53, and his teenage son, unlike Bobby, had no sympathy for the aches and pains of a whiny parent. “If my pacer had done to a dog what he did to me in those last ten miles, he’d be in jail right now.” See, Bobby? This is what a pacer does. Bobby shakes his head. I can tell he is crossing pacing skills from his list of life ambitions. Eric crossed the line in a 24:05, disappointed but only for about a nanosecond. Anyone heard from Rachael? Nada. Zip. I worry. It’s been the second hottest Western States on record. Gordy dropped out at mile 55. Tim Olson won. What a beast. Ian looks comparatively fresh. His race ended when he missed the cutoff time at mile 62, but we think he still deserves an award for making it that far as the only one in his age group. Still no word from Rachael. We replenish with heaping platters of eggs and bacon to give us a last bit of energy for the award ceremony when she drags herself in our direction, her right leg bloody and bruised from a fall during the early miles, her face a grimace of disappointment. She struggled through pain, dehydration and heat exhaustion for twenty-eight hours to a hard-fought and heartbreaking DNF at mile 90. An effort to be proud of, but not the same thing as finishing. On the bright side, none of us has ended up in the hospital, or the obituary pages. There will be other ultras, and other stories. Leadville is seven weeks away.

It is a good time to be alive and running.

Like this:

Like Loading...