“Human beings, who are almost unique in having the ability to learn from the experience of others, are also remarkable for their apparent disinclination to do so.”

Douglas Adams

The Chimera is a monstrous creature from Greek mythology. Equipped with sharp fangs, pointy horns, and deadly venom, she intimidates even courageous souls. The Chimera 100 is a race that takes place every November in the Saddleback Mountains near Los Angeles. It’s named Chimera for a reason: 22 000 feet of elevation gain, technical terrain, sparse course markings, 13 hours of darkness, and the likelihood of extreme weather conditions. Of course, I couldn’t wait to sign up for this monster of a run. My husband can’t take time off work, so I have made the courageous decision to face the beast alone, without crew or pacer or other support. Wait, this is not entirely true: Rachael StClaire, my friend and training partner, is also running the Chimera. We will share the experience, the pain, and the hotel room.

I am paranoid about flying to ultras, mostly because I like to pack for all possible conditions and emergency situations. My foam roller, my sleeping bag, my rain gear, 15 different warm layers, 5 different head lamps requiring three different types of batteries, three stashes of extra batteries, a large duffel bag full of nuun, clif bloks, water bottles, stinger waffles, traumeel, ice packs, etc etc. The prospect of stuffing this pile of items into two regulation-weight suitcases is too daunting to consider. Besides, airlines lose luggage all the time, which would spell disaster. No, a road trip is the way to go.

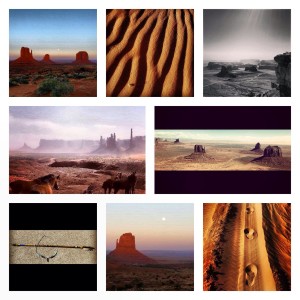

I set out on my solo expedition on Thursday after work, heading South and then West. The drive takes 13 hours. I make it to Holbrook, Arizona before stopping for the night. On Friday, I arrive in Lake Elsinore at 4 p.m, in time to meet RD Steve Harvey, a few of his friends, and his pet skeleton at a biker bar named Hell’s kitchen for packet pickup. The evening is filled with familiar pre-race rituals. Like two seasoned gladiators preparing for the arena, Rachael and I know what to do. We pack, then re-pack our drop bags, color-coordinate our outfits, charge our Garmins, and study the course maps and the turn-by-turn directions.

After a few hours of sleep, we head on up the Ortega Highway. Bluejay campground is our home base. From here, we will face the beast. At 6 a.m., under 111the first light of dawn, we head out the first of two out-and back sections. Down to Cocktail rock, where enthusiastic volunteers offer, among other assorted goodies, the best homemade pumpkin pie ever tasted at an ultra. I devour two pieces, which gives me energy for the climb back up to Bluejay.

The good (or not so good) thing about out and backs is that I know how many women are ahead of me. Nikki Kimball is in the lead, no surprise. Then no three, no, wait, four more. I get ambitious and pass two of them by mile 15, before the sobering realization that we still have over 80 miles to go slows me back down. It’s better to conserve some energy. But back at Bluejay, the fourth place woman leaves just as I arrive. I am in such a hurry to catch her that I head back out after refilling my camelbak, and realize about a mile later that my salt tabs, and my clif bloks, are still in the drop bag, where they won’t do me much good. No nutrition for the next ten miles. Not smart. I briefly debate turning around, but my beast mode is in high gear. A familiar silhouette moves in my direction. Rachael, finishing her first loop, behaves like a true ultra friend. She hands me four of her salt tabs, without expecting an explanation of why I need them only a mile out of the aid station.

I pass another woman, then a woman passes me. It’s Nikki Kimball. A bummed Nikki Kimball. What? Why is she not miles ahead? She explains that a #)*&%$-hole has moved the course markers at an intersection, an intentional act of trail sabotage. She has run quite a few extra miles, and intends to drop out at Candy Store. I commiserate, and I’m beginning to see Steve’s point. It’s better to have no course markings than to have course markings leading in the wrong direction. Matt Gunn catches up with me a few minutes after Nikki does. He is in the same situation. We arrive at the Chiquita Falls aid station, which supposed to be water only, but — bless their hearts — the lovely volunteers have hauled in some food. I am saved from looming starvation! I don’t have to pay for my Bluejay stupidity! Relieved, I fill a ziploc baggie with assorted goodies and leave, mumbling sincere thank-yous with a mouth full of pretzel stix. Interesting conversations make the miles fly by. Matt and Nikki eventually take off at lighting pace, but on the way back from Candy store, I chat with Saravanan, originally from India, who is running his first 100 and is bubbling over with energy. Later, I catch up to Matt Smith, still holding back wisely at this point in the race. He later finishes a smoking fast third. And I catch up to the second-place woman, who is feeling ill and has slowed to a walk.

I reach Bluejay around 4 p.m., feeling strong. It’s still pleasantly warm, but it’s also November, and the night will start very soon. While a kind aid station saint doctors a blister on my left foot, I contemplate continuing in my skirt. We’re in Southern California — how cold can it get? Another saintly Bluejay volunteer (my brain is mush by this point, and I can’t remember names, otherwise I would thank specific human beings) tells me in a stern voice to put on the warmest layers I brought: tights, gloves, hat. She sounds like she knows what she is talking about, and in spite of — or maybe because of — my mushy brain, I comply. A smart decision, as it turns out. The toughest part of the course is still to come. I head into a leafy tunnel on the way to Holy Jim. Twilight envelopes the trail. Time to turn on my head lamp. The trail ends, and I backtrack for a few minutes, until I find the corresponding spot in the direction sheet. The missed turn only sets me back a few minutes. Animals rustle in the dense forest. I imagine deer, birds, even bears and mountain lions. It’s a consolation that ultra runners smell so rank after 12 hour on the trail that no self-respecting predator would be desperate enough to put one of us on the dinner menu.

I am alone now, in the cool, dark evening. 55 miles are behind me, but the long night still lies ahead. The dying light feels peaceful, serene even. I settle in for the long climb up Santiago Peak. A cold wind blows on the mountainside, and I mentally thank my guardian angel from the Bluejay aid station who insisted I put on long sleeves, and long pants. Mile 65. There are headlights up ahead, and as I come closer, I realize it’s Sada, the leading woman. Her knees and elbows are bleeding from several falls, and she looks like she’s in pain, but, tough cookie that she is, she marches on in spite of it. I’ve been in that situation, when bruises settle in, making each step a little bit more of an effort than the one before. We exchange greetings, and I move ahead, aware of the 35 miles left to cover. A lot can happen in 35 miles. The wind is howling. My stomach is still cooperating, but it’s getting tired of clif bloks, no matter the flavor. I decide to be adventurous and replace them with much more varied and interesting aid station offerings: potato chips and ginger ale at Bear Springs, quesadilla pieces at Maple Springs, chocolate chip cookies and ramen noodles at Indian Truck Trail. Against all odds, my stomach stays happy. Maybe it remembers my undergraduate student diet from over two decades ago. Maybe it feels nostalgic. Whatever the reason, I feel great — moving through the cold, blustery darkness, following the beam of my head lamp. The night is clear: a sliver of waxing moon, stars dotting the black sky. Against this backdrop, the views of the LA metro form a spectacular contrast. Millions of people live down there, in that glittering ocean of orange light. Most of them have no idea that a few crazy ultra runners are climbing around on Santiago Peak, just a few thousand feet above them. My Garmin has died, and I have no idea how many hours have passed, but even that doesn’t matter. Time is irrelevant. I run, left foot, right foot. What else do I need? Oh, yeah, my turn by turn directions. Very handy. I’m still on the right trail, from what they say.

On the long downhill toward Corona, I fall, but land in a sandy spot. Other than looking like I’ve been dusted with flour, I continue unscathed. Mile 84. Corona aid station, a cheery spot in the darkness. The seven-mile climb back up to the main divide seems to take forever. Fatigue settles into my legs, which begin to feel heavy. But only a few miles are left. Nine more from Indian Truck Trail. One more big uphill. It’s still dark. It’s still windy. Another aid station, in a tent perched on the hillside, hardy volunteers braving the elements. It looks like it will blow them away any minute. Three more miles. I make a deal with myself: walk all uphills, run everything else. I imagine Sada, not far behind me. I also imagine what my husband, an excellent pacer, would say right now: “That’s not really an uphill. Run! That’s almost level. You call this an uphill? Nope, it’s not. Stop arguing.” I keep running. I begin to fantasize about the finish line. Just a couple more miles. There’s a paved road. The campground entrance. The first hint of dawn on the horizon. Wait, where is that finish line? The road ends. I pull out my turn-by-turns one more time. “Finish on paved road in Bluejay campground.” This doesn’t help. I turn around. There are orange flags leading down a narrow path named Falcon trail. Relieved, I follow them for a few minutes. They seem to be leading nowhere. It’s another case of trail vandalism, surely. A cruel trick at mile 99.5. No, I’m smarter than that. I turn around, back onto the paved road. I backtrack for a while, looking for directions, reading and re-reading the last of the turn-by-turn instructions. A mystery. I explore another paved road. Doesn’t look right. The early morning light brings no enlightenment. The driver of white jeep finally does. Lady, you need to backtrack and go down the Falcon trail. Didn’t you see the flags?

Oh. Duh. Just another case of 100-mile paranoia. I’ve been known to suffer from delusions involving not just moved trail markers, but conspiracy plots, axe murderers, and piles of severed heads. I back-back track, follow the bright orange ribbons, finally reach familiar ground, and eventually the finish line. To my surprise, I’m still the first woman to run across it, in 23:48, extra lap around the campground and all. Steve, more sleep-deprived than any of us runners, looks remarkably alert as he hugs me and hands me the gorgeous Chimera buckle.

Nothing compares to the feeling of weary, deserved exhilaration that comes with crossing the finish line of a 100-mile race, especially one as tough as this one. Except, possibly, seeing other people cross it, which is why I love hanging around until the last runners finish. I listen to their stories, and share mine. We bond over the world’s best cheeseburgers and beer. Matt is basking in his top-three glory. Sada perseveres to a strong third-place finish, bruises and all. Saravanan comes in, slower than anticipated, but beaming. Rachael finishes in 31 hours and change, looking strong. Steve hugs every sweaty, stinky finisher. I’m not given to sentimental episodes, but come close to feeling emotional. I’ve come to California, knowing a grand total of one other person in this race. 31 hours later, I’m among friends, among people who share a crazy dream, and maybe a tad of OCD. Others may not understand us, but we sure understand each other.

Thank you, Steve and Annie Harvey, for making this race come alive. Thank you, everyone who graciously donated their time, their sleep, their sanity to work at an aid station. Thank you, all the runners I shared miles with, for making the miles fly. Thank you, thank you, thank you. I am a lucky woman, and it’s a good time to be alive and running.

Like this:

Like Loading...